New research from Canadian scientists suggests life on Earth began in warm little ponds after meteorites splashed into them about four billion years ago.

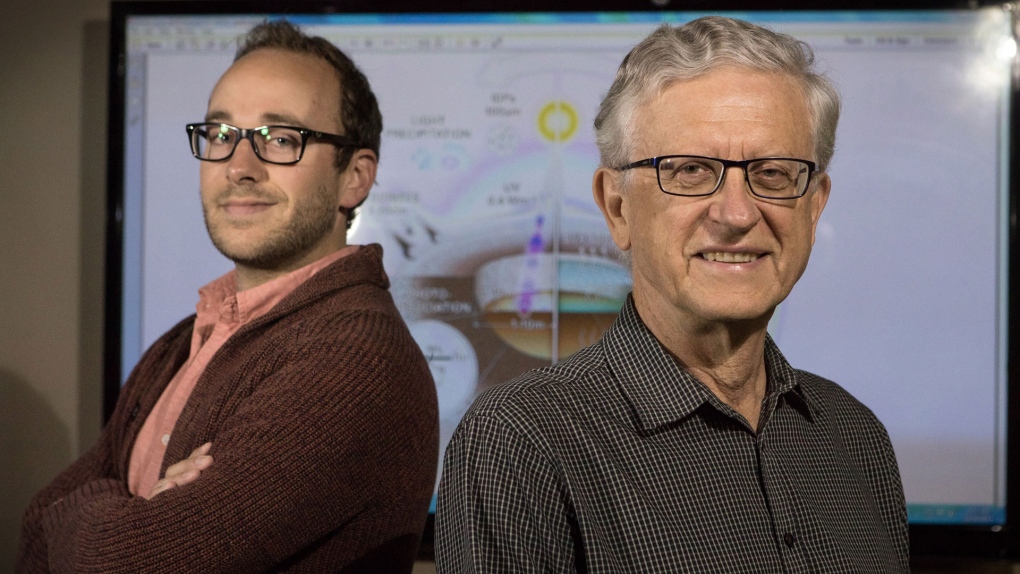

A McMaster University graduate student and his professor said they have run the numbers for the first time on a theory from Charles Darwin in the 1870s that suggested warm ponds were the breeding grounds for the first life forms.

Their calculations suggest meteorites bombarded the earth and delivered the building blocks of life that then bonded together to become ribonucleic acid (RNA), the basis for the genetic code.

Ben K.D. Pearce, a PhD student at McMaster, said he was having a conversation about interplanetary dust with a colleague while in Germany when inspiration struck.

"We can do a calculation here and actually find out whether interplanetary dust or meteorites could deliver enough organics -- building blocks of RNA -- to reach high concentrations within ponds," he said.

On a train to Berlin, he did more calculations. Then over the course of more than a year at McMaster he crunched more numbers from previously published data from a wide variety of fields in a way that he said has never been analyzed before.

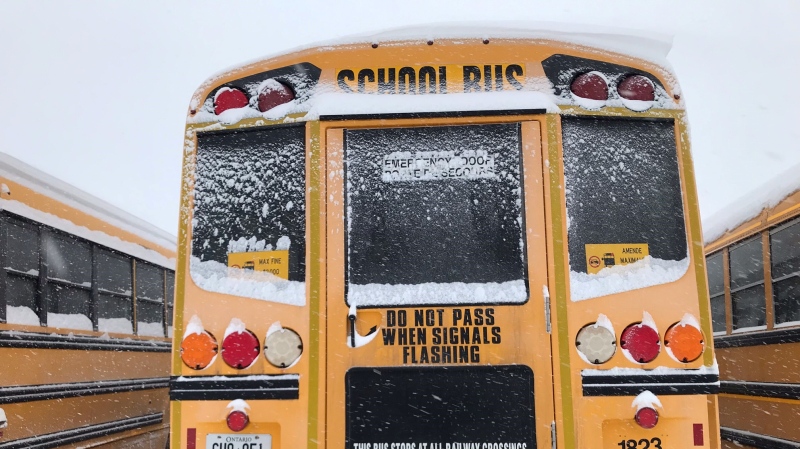

He added in more components including the effects of wet-dry cycles, ultraviolet radiation, drainage of ponds, precipitation and evaporation.

"We expanded this model so it encompassed all facets of science," Pearce said.

The results, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest the plausibility that life began in warm ponds.

It also suggests the other theory on the beginning of life is wrong. That theory postulates the building blocks of life came about through vents in the earth's crust at the bottom of the oceans.

"That theory has an irreconcilable problem where it can't seem to make chains of RNA because it's permanently in water," Pearce said.

The wet-dry cycles -- when ponds dry up and are then filled up again through precipitation -- were a necessary component for allowing the creation of RNA polymers, basically long chains of RNA molecules bonded together.

The results expand on work done in the 1990s by Carl Sagan that showed interplanetary dust and meteorites were a crucial component of providing the genetic building blocks forming life on earth.

The work by the McMaster researchers, along with their collaborators at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, theorizes what happens after that point.

"Nobody's put this together and tried to build a theory that's truly interdisciplinary," said Ralph Pudritz, Pearce's professor at McMaster. "This is tremendously exciting!"

Pudritz and Pearce are excited to test their theory next summer when McMaster opens an origins-of-life laboratory.